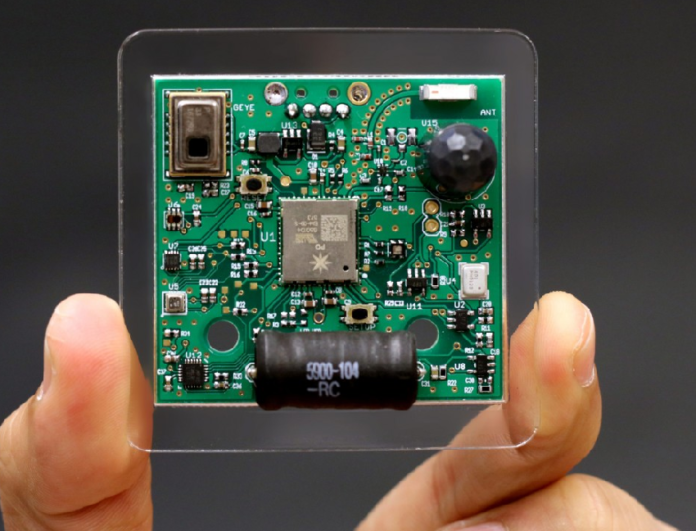

Gierad Laput wants to make homes smarter without forcing you to buy a bunch of sensor-laden, Internet-connected appliances. Instead, he’s come up with a way to combine a slew of sensors into a device about the size of a Saltine that plugs into a wall outlet and can monitor many things in the room, from a tea kettle to a paper towel dispenser.

Laput, a graduate student studying computer-human interaction at Carnegie Mellon University, built the gadget as part of a project he calls Synthetic Sensors. He says it could be used to do things like figure out how many paper towels you’ve got left, detect when someone enters or leaves a building, or keep an eye on an elderly family member (by tracking the person’s typical routine via appliances, for example). It’s being shown off this week in Denver at the CHI computer-human interaction conference.

While it’s not yet a consumer smart-home device, it was pretty accurate in his initial tests. His team is now stress-testing the 100 units manufactured so far. Laput says they cost about $100 apiece to make right now, but he thinks that could be cut to about $30 if they were manufactured in high volume.

Laput says he and fellow researchers were curious to see if they could find a compact, capable alternative to existing smart gadgets, which can be costly and don’t always play nice with each other, and wireless smart tags, which have to be stuck to various things around the house. They also wanted to see how much sensing they could do without a camera, which their research showed people found invasive.

To try this out, the researchers put together a sensing board that can track motion, sound, pressure, humidity, temperature, light intensity, electromagnetic interference, and more.

“Because we have so many different facets, it gives us flexibility to sense a wide array of events,” Laput explains.

The researchers placed five of these super-sensors in a building—one each in a kitchen, office, common area, classroom, and office—and let them run for two weeks. In the kitchen, the sensing board could detect things like a sink running or a paper towel being dispensed; in the office it could track knocks on the door; in the common space it detected when coffee was brewing and the microwave running or having its door opened or closed.

A video the researchers made illustrates a bunch of these activities, showing how the raw data captured by the sensors is classified into different events with the aid of their proof-of-concept software.

The accuracy of the project was pretty high, but it would probably need to be improved to create a consumer product. Over a week of training and testing, 38 sensors in five different locations were 96 percent accurate, on average. This crept up a bit to 98 percent after another week, but even at that rate users could be turned off by false positives.

By: Rachel Metz

Source: www.technologyreview.com